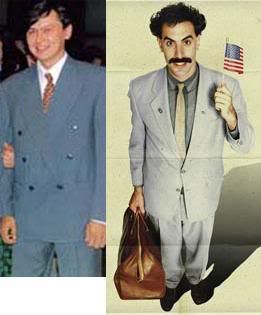

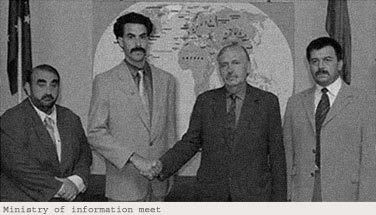

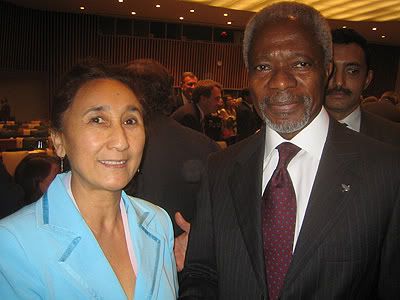

Rakhat Aliyev from 1990s (left) and Borat today (right)

As the PR surrounding the Borat movie approaches a fever pitch ahead of the film’s worldwide opening on November 3 of this year, more and more articles are written about the reaction of the Kazakhstan government to the Borat figure and his portrayal of its country. Most western observers are amused by the outrage that the Kazakhstan government has expressed over Borat, but the ire of Kazakhstan’s officials is more understandable to those who have spent extensive time in the country. Borat bears significant meaning for the Kazakhstan ruling elite regarding their personal development and the development of the country as a whole. In other words, to understand why the Kazakhstan ruling elite has such a visceral reaction to Borat, one needs to understand from whence the Kazakh elite has come, where they are now, and where they wish to be in the future.

Borat at the fictional version of Kazakhstan's Ministry of Information, 2006

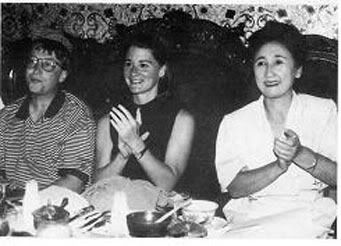

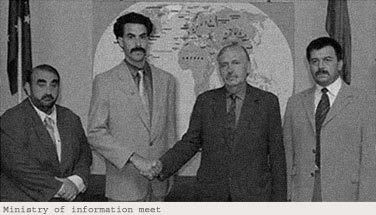

James Giffen (left), Sara Nazarbayeva (center), and Nursultan Nazarbayev (right) in Manhatten during the 1990s

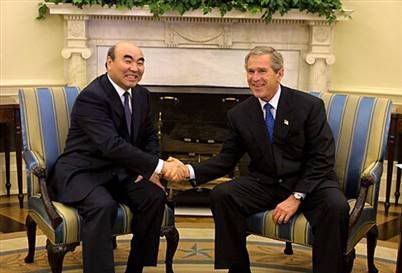

The character of Borat is not about Kazakhstan per se. He is about that time in history after the U.S.S.R. fell and when its newly independent successor states were first engaging the world after decades of isolation. In other words, Borat is a satire of the former Soviet Union (FSU) of the early 1990s, Kazakhstan included. The pictures above are telling: Rakhat Aliyev in a double-breasted suit and President Nazarbayev wearing a short tie with his now-indicted former advisor from the U.S., James Giffen. This is from whence the Kazakhstan elite has come in the last fifteen years. In the early 1990s, Kazakhstan did not enjoy the respect of the international community. Instead, it was seen as a backwater and under-developed country that happened to be rich in resources. It was in this context that the President of Kazakhstan found

a slippery middleman by the name of James Giffen to help him engage western oil companies. And, it was in this context that

President Nazarbayev and his close associates allegedly took bribes passed through Giffen in the form of cash, snowmobiles, school tuition for their children, and other “gifts.” Today, as Kazakhstan is emerging as an energy “player” on the world stage, the early 1990s likely evoke embarrassment on the part of many in the Kazakhstan elite. Borat is a satirical reminder of that time, and, while the character is primarily meant to mock the geographically challenged nature of Americans, many in Kazakhstan’s elite take him as a personal affront about who they once were.

Today, Kazakhstan is an emergent energy power in the world. It is also becoming a geopolitical player in the sensitive region of Central Asia, caught between Russia, China, and the volatile Muslim states of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. In that context, the country and its elite want most of all to be recognized as a reliable and progressive influence on the region, a power broker that can balance the strength of Russia and China with that of the Muslim world. The country’s elite has already exchanged its short ties and double-breasted suits of the early 1990s for Gucci and Armani suits with conservative cuts and silk ties from Italy. Their children study in the best boarding schools of Europe and the United States. They vacation in the alps and in the south of Spain. Instead of taking bribes through middlemen, they are placing their assets on the London Stock Exchange. Indeed, Borat’s character at first glance seems out of place in the context of Kazakhstan’s booming oil economy.

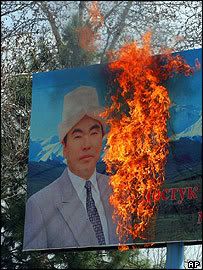

Borat’s unsophisticated character, however, still shares something with the segment of Kazakhstan’s elite that emerged from the Soviet Union. This “old guard” in Kazakhstan’s elite still does not really understand or believe in the principles of a “rule of law,” “human rights,” and “representative government.” While Borat’s follies are more about “political incorrectness” with regards to women and ethnic minorities, his sometimes violent and always uncouth behavior as well as his blatant dismissal of a “rule of law” are also a satire of the character of Soviet (and post-Soviet) authoritarian rule. This is the role Borat is playing when he says “please come see my film, if it not be success, I be execute.” This is the part of Kazakhstan that Borat’s character still represents. There has yet to be an election in Kazakhstan that has been deemed free and fair by international observers; there continue to be politically motivated arrests without due process; the media is controlled by the state and the president’s inner circle; two opposition politicians were found dead within the last twelve months, and the investigations yielded results that were not accepted by most Kazakhstanis as legitimate; public protests are stifled in the country; opposition political parties are under constant harassment. If Kazakhstan has changed significantly in the economic sphere since the early 1990s, it has changed quite little politically since that time.

It is precisely this disconnect between economic and political reform that draws criticism of Kazakhstan from western governments and human rights organizations. Because they do not really believe in democracy and human rights, however, Kazakhstan’s “old guard” seems to think it can avoid international criticism through public relations campaigns rather than through real reform. They place inserts in the New York Times and the Economist to hail the country’s democratic accomplishments, they pay for television spots, and they hire expensive Washingtion political PR firms to do spin control. The problem is that all of the money in the world (or at least that amount available to Kazakhstan’s elite) cannot really replace reality with perception. Kazakhstan’s “old guard,” thus, retains much of Borat’s character no matter how much they try to hide it. That is why they hate Borat so much—because he is a part of them.

That being said, there are others in Kazakhstan’s elite who are not as outraged by Borat. They view the satire as being a joke about Americans and Europeans, whose ignorance of Kazakhstan and the rest of the world they frequently encounter. To such people, many of whom want to reform Kazakhstan politically, Borat may also reflect a satire of the aspects of their political culture the Soviet Union bequeathed Kazakhstan. In such reformers’ vision for the future of Kazakhstan, Borat will no longer have any relevance. If that vision comes to pass, all Kazakhstanis will be able to more comfortably laugh about the entire Borat escapade. Until then, however, Borat is a bitter reminder that Kazakhstan is not yet accepted as a member of the club of liberal democracies in our present world order.