What about the “Freedom Agenda”? (it had to be said): Nazarbayev’s Visit and the Contradictions of Bush’s Foreign Policy

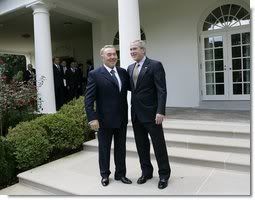

Recent pictures from President Nazarbayev's state visit to the U.S.

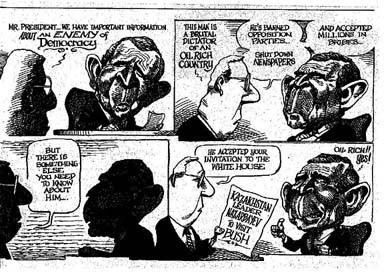

It had to be said. With the attention to the Borat stunts, the Kazakhstan boosters’ op-ed pieces, the spots on network television, the newspaper advertisements placed in the New York Times and the Washington Post, and the unveiling of the new Golden Man statue in Washington, DC, it almost seemed like the issues of democracy and human rights were going to quietly disappear during President Nazarbayev’s visit to Washington. The other side of the story, however, is starting to come to the forefront as Nazarbayev’s visit winds down. An article in the National Review lambastes the Bush administration for embracing Nazarbayev, calling the country a “façade state.” Ken Silverstein continues his string of investigative pieces on Kazakhstan’s interest peddlers in Washington (and inside the U.S. government) in an article co-written by Sebatian Sosman for Harper’s Magazine that is particularly condemning of the U.S. side. The most condemning news opinion of the day in terms of its influence, however, came from the Washington Post’s editorial page. A day after running Fred Starr’s appeal to ignore Kazakhstan’s human rights and democracy problems and on the same day that the Kazakhstan government had bought two advertisements in the paper’s first section extolling Kazakhstan’s accomplishments and its friendship with the U.S., the Washington Post’s lead editorial was a scathing condemnation of Bush’s “embrace for a strongman” (i.e. Nursultan Nazarbayev) in the context of Bush’s own second inaugural address that unveiled his “freedom agenda,” where he had pledged to “end tyranny in our world.” Aside from briefly highlighting such issues as Kazakhstan’s electoral record and the infamous “Kazakhgate” bribery case, the piece questioned the rationale of welcoming Nazarbayev while ignoring his human rights and democracy record.

Personally, I am not in total agreement with the Washington Post’s analysis that Bush should not have welcomed Nazarbayev to the White House, but it had to be said, and its points must be a part of the discourse on Kazakhstan because that is the way American democracy works. Different interest groups lobby their own special interests, and, hopefully, policy follows the rational route in between where agreement can be made. It would, of course, reflect better on the United States if the debate had taken place before President Nazarbayev’s visit so that the Bush administration could have taken the appropriate steps to engage Nazarbayev this week while simultaneously accenting the country’s dire need for political reforms.

I believe that the U.S. should engage Kazakhstan, and it would be shortsighted to ignore this country, which, in addition to its strategic position, has accomplished many great things from liberalizing its economy to voluntarily disarming itself from nuclear weapons, all in the fifteen years since its independence from the Soviet Union. Engaging Kazakhstan without a discussion of political reform, however, is equally if not more shortsighted. Kazakhstan could be on the verge of great things in the world and become a shining example of sustainability, stability, and democracy in Central Asia and the Muslim world as a whole, but it could also be on the verge of instability and dictatorship. Nursultan Nazarbayev has shown himself to be one of the great leaders of the former Soviet Union by transitioning his country from the periphery of the U.S.S.R. into a global player economically. He, however, is also a man of his time, and that time is waning. Nazarbayev is not immortal, and there will eventually be a need for a succession of leadership in Kazakhstan. His successor will not have the luxury of dealing with the low expectations that Kazakhstanis held for the future when the Soviet Union fell. The people of Kazakhstan will increasingly desire protection under a legal system they feel is not corrupt, and they will demand government services that are accountable to the public. Businessmen, big and small, will also require that its state’s legal system can protect them from hostile takeovers and intimidation by influential people in the country. Most of all, the people of Kazakhstan will eventually demand to have a say as to who runs their country and who manages their common natural resources.

In the context of Kazakhstan’s economic development, sophisticated financial sector, relatively diversified wealth, and emerging civic pride, such changes are not out of reach. At least for now, political liberalism in Kazakhstan will not lead to the victory of Muslim radicals with anti-American sentiments as might be the case in Pakistan or as was the case in Palestine this past year. Kazakhstan likes to compare itself to the “Asian Tigers” of the 1980s, but those countries have also largely changed courses over time. The question is whether Kazakhstan will follow strongman stability towards stable democracy as in South Korea or whether it will implode into power struggles as happened in the twilight of Suharto’s regime in Indonesia. If Kazakhstan chooses the right path, Nazarbayev will undoubtedly go down in history as a Central Asian Ataturk who established a western-style system from the ashes of an empire from another age. If it doesn’t, Nazarbayev may just be remembered as another post-colonial strongman who helped his country develop temporarily. Furthermore, if Kazakhstan does adopt a path of political reform, it will be better placed to play a decisive role in the development of stability in the entire Central Asian region.

In order to follow the more stable path towards political reform, however, Kazakhstan needs to begin now to undertake the difficult reforms that would allow it to be ready for a fully democratic transition of power in 2012 when Nazarbayev’s present term ends. Before having a democratic presidential election in 2012, the country needs to do serious work to ensure free and fair elections at lower levels of government, including parliament (to date, every election in Kazakhstan has been a great disappointment). It also needs now to begin reforming the court system to ensure that verdicts cannot be bought or swayed by political influence without serious consequences. Finally, Kazakhstan needs to allow for free expression and free access to information to ensure that the process of reform can involve the full range of voices and opinions in formulating the future course of the country. These were all things at least indirectly highlighted in statements by Kazakhstan’s opposition this week as a group of opposition political figures outlined a series of demands to be levied by the U.S. and other OSCE member-states on Nazarbayev in exchange for the OSCE chairmanship he covets. This week could have been the opportunity to engage these questions in a serious way as part of conversations aimed at cementing a longer-term strategic partnership between the U.S. and Kazakhstan. If that had been done, I don’t think President Nazarbayev would have dismissed the appeals for reform out of hand because it is my understanding that he hears the same pleas from a progressive segment within his own elite.

That, however, does not seem to be what is happening in the bilateral meetings that are taking place in Washington this week. Instead, most reports, including congressional testimony in the senate and the White House’s own press statement, suggest that both sides quietly talked about common strategic interests in energy security and fighting terrorism without touching the difficult question of democracy. If that is the outcome of the meetings, it will have been an opportunity missed both for the U.S. and for Kazakhstan. The problem is that the Bush administration cannot have it both ways. It cannot demand radical regime change in some authoritarian states in the name of a global “freedom agenda” while ignoring democracy in other cases for strategic reasons. A much more reasonable approach would be engagement with all countries combined with targeted pressure and encouragement for the political reforms that will make places like Kazakhstan and the world more prosperous and stable over the long term. Without a coherent and consistent policy of engagement on democracy and human rights, the vocal statements that President Bush makes about “ending tyranny in our world” end up sounding to people around the world as merely a selectively used, but insincere, instrument to justify U.S. economic and political interests.