A Conversation with Steve Levine, author of "The Oil and the Glory"

This post is a first for the Roberts Report – an exclusive interview. Steve Levine, author of the recently released book

"The Oil and the Glory", agreed to answer some questions for me about current events surrounding oil and politics in the Caspian region, a topic which is the focus of his new book. I first met Steve Levine in the late 1990s when he was covering Central Asia mostly for the New York Times. At that time, there was no international correspondent as well informed about Central Asia, and especially about Kazakhstan, than Levine. He always struck me as one of those archetypical journalists who followed stories every waking moment of the day. Even when Steve was out socially, he was always tracking down tidbits of information. In Kazakhstan, of course, Levine is best known as the journalist who broke the infamous “Kazakhgate” story, which implicated Nursultan Nazarbayev in allegedly taking bribes from international oil companies. His newly released book, "The Oil and the Glory," delves into the Kazakhgate case some more and provides a fascinating profile of James Giffen, the American citizen and once close confident of President Nazarbayev who presently awaits trial in New York for his involvement in the “Kazakhgate” corruption scandal. "The Oil and the Glory," however, is about more than Kazakhstan and “Kazakhgate.” It is an engaging narrative of the politics of oil in the Caspian from the boom-town days of late nineteenth century Baku to the calculated madness of Turkmenbashy and beyond. All in all, it is a great read and is recommended to anybody interested in Central Asia today. Book plugging aside, let’s hear what Mr. Levine has to say about some of the burning issues facing Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan today.

------------

SR: James Giffen figures prominently in your book, and you were the first journalist to report on his alleged corrupt practices in Kazakhstan. What are your thoughts about why the case has been continually postponed?

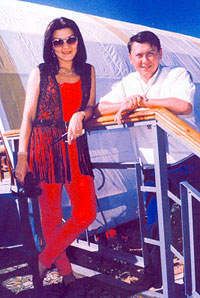

James Giffen (left) with Sara and Nursultan Nazarbayev in New York during the 1990s

S.L.: Initially the delay was deliberate. Giffen’s lawyers mounted their remarkable defense – not denying that Giffen shifted the $80 million or so to Nazarbayev et al, but saying that because he was of such use to American intelligence agencies, they had given him the impression that they approved of the entire operation in order to keep him on the inside. The defense calculus, of course, was to play into the Bush administration’s pathological secrecy, slow down the game and ultimately get the Justice Department to drop the most serious charges rather than disgorge sensitive documents demanded by the defense.

I say initially, because now it seems that the prosecution, too, is delaying. It keeps filing secret motions that require long periods of consideration, and have forced the suspension of two straight hearings (the last being Friday, Oct. 26th). Judge Pauley, once ultra-anxious to get the trial going, seems resigned to this holding pattern. There is no sign of a trial any time soon – meaning any time in the next six months or probably longer.

Why would the prosecution delay? Your guess is as good as mine. Perhaps the prosecutors hope that the next Justice Department and CIA will stop meddling in the case, so it can go forward.

The dark conclusion would be that the prosecutors are, like Giffen’s lawyers, looking for interest in the case to wane so that some of the more serious charges can be dropped. But I doubt that’s the case. There is a lawyerly dance going on to which layman are not privy, and need some help to understand.

S.R.: What is your opinion of Giffen’s defense that he was assisting the CIA and, thus, should not be prosecuted?

S.L.: Giffen’s relationship with the CIA goes back to 1970 or so, when he was a young middleman training under the master salesman to the Soviets, Ara Oztemel. As a price for being able to do business with Moscow, people like Oztemel, and by extension Giffen, had to brief the agency when they got home from trips to the Soviet Union.

That relationship persisted through the Soviet period, as Giffen continued to usher American businessmen to Moscow. It carried over into other departments and agencies, for instance in the Bush I administration; Giffen had a close relationship with some of the Bush I officials because of his long intimacy with the Kremlin.

After the Soviet breakup, however, things become murkier. Giffen lost his Kremlin contacts, and moved on to Kazakhstan. He was promoting himself as the go-to man all over again, and one device was mystery. He routinely dropped hints of an insider relationship with the CIA into his conversations, giving the impression that he was highly valued by the agency.

The truth was that he was still briefing the agency, the National Security Council and so on. But it began to be unclear at whose initiative these meetings were taking place, and who valued them more – Giffen or these officials. After all, the impression of some Bond-like affiliation gave Giffen cachet in Kazakhstan.

Of course Giffen was a master at dropping insider information (about the Kazakhs) into his conversations with the CIA and NSC, too, so they couldn’t help but be intrigued. Yet they also began to be annoyed by his presumptuousness, and began to keep an arms’s length. They would listen, but not necessarily engage. Some would not listen at all.

The question here is – does this whole history amount to an agency-client or agency-asset relationship? Did the NSC or CIA regard Giffen as their man, or a man, on the inside, one whose activities were to be sanctioned in order to retain access and influence with Kazakhstan?

I personally am skeptical. Giffen was inarguably an important influence with the Nazarbayev circle. But I find it hard to believe that anyone in a position to do so gave Giffen an anything-goes green light, in whatever form.

As evidence, why were the payments to Nazarbayev’s accounts split up into small, $5 million pieces before being reconstituted in his account? If they were straight-forward payments, and believed to be approved by American intelligence agencies, why not simply send a single payment and not risk appearing like a money-laundering operation?

S.R.: Do you think Giffen will ever be convicted? If so, will it affect President Nazarbayev’s popularity in Kazakhstan?

S.L.:One cannot predict what will happen in a courtroom. Look at the trials from the swinging dotcom 1990s.

In the beginning of Giffen’s case, the prosecution seemed to have an open-and-shut case, yet it’s been delayed now for three-and-a-half years. In addition, one can’t underestimate Giffen himself. I have been subject to Giffen’s charm, and I can tell you that he is fully capable of pulling the entire courtroom along with him. How he would respond under hostile prosecutorial questioning is another matter; he has a habit of arrogance and petulance, and might not be as appealing when challenged.

If he is convicted, there will be an impact in Kazakhstan, but I don’t think popularity is the measuring stick. Does popularity really matter, after all? Nazarbayev is in fact the invisible man on trial – he received much of the payments, and hence were Giffen to be convicted, it would be the president convicted, too.

A fact-based, open courtroom judgment against Giffen, hence Nazarbayev, would be a stunning setback in credibility for Nazarbayev. Nazarbayev already has lost much of the smooth, teflon veneer that made him appear positively benign next to Central Asia’s other leaders. He would be able to continue to lead, but the ruling family’s resemblance to the Suharto clan would become plainer.

S.R.: You also highlight Turkmenistan in your book. What are your thoughts about his successor, President Berdimukhamedov? Will he open the country and its oil and gas up to the world and foreign investors?

President Berdimukhamedov of Turkmenistan

S.L.: I do think he will open up in this regard. But the bigger question is whether he stands up to Russia and commits to building a trans-Caspian pipeline. Were he to do that, the geopolitical balance on the east Caspian – and really on into Europe – would shift. At once, both Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan too, would have the prospect of a lifeline independent of Russia. And there would be an alternative natural gas supply for Europe Will he? That’s conjecture, but I have a feeling he will.

S.R.: There is much noise lately about how the Kazakh authorities are dealing with the Kashagan project. Do you think they are justified in their actions?

An off-shore well at the Kashagan site on the Caspian

S.L.: Absolutely.

Eni, the Italian operators of the field, has been inept, and the other big oil companies involved have failed to take charge; if Eni can’t get the field going, its partners should by now have put another of their ranks in its place, like Exxon or Total. The project is already five years late, and I believe that’s optimistic; and it’s more than twice over budget (although that’s predictable – the cost of oilfield development around the world has in fact gone through the roof). Kazakhstan ire is fully justified. I also think that, in comparison with Russia, Kazakhstan has been measured.

What will be interesting is what happens with Kazakhstan’s other two fields – Tengiz and Karachaganak. I suspect that the Kazakhs will seek important contract concessions in those two fields down the road, too.

S.R.: Oil has often been seen as the kiss of death for stability and progress in the developing world. How do you think the countries of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan will handle its oil in the future? Will any of the countries succeed in using their oil money to establish stable economic growth and political systems over the long term?

S.L.: Let’s go country by country. Azerbaijan could have been on a stable path but started too late. Unfortunately, I believe it is in its peak years right now, and unless something extremely dramatic is done in terms of diversification – unlikely I think – it will then go into economic decline, starting in the middle of the next decade or so.

Politically, when you say stable I assume you don’t mean the current stability, but one involving a truly elected leadership. I’ve always thought that the next generations of all the Central Asia and Caucasus republics could be much different from today, which is what makes the independent pipelines so important in providing them an economic lifeline, and thus the luxury of genuine choice. Politically, Azerbaijan is in this group of potential change down the road, but we are talking far in the future.

Turkmenistan is the dark unknown. There is no sign of coming prosperity or a different political system. Yet I’m optimistic about it, not because of hard evidence, but a hunch. Let’s talk again in five years.

Kazakhstan has the best prospects, mainly because it’s the richest in terms of resources – I think the middle class will continue to grow, and that it’s the most likely not to plunge into Dutch disease. I also think it has the best chance of a different political system. There is a class of businessman-politician in Kazakhstan that doesn’t exist in the other two republics; once Nazarbayev is gone, there’s a reason to believe that people like them will take charge and allow Kazakhs to choose their own leaders in a free manner.

S.R.: When you worked in Kazakhstan, you followed the career of Rakhat Aliyev and the entire Nazarbayev family. What do you think of the recent warrant for Mr. Aliyev’s arrest? Does it mark a new stage in Kazakhstan’s politics, or is this just business as usual?

Rakhat Aliyev and Dariga Nazarbayeva (the early years)

S.L.: Aliyev crossed some invisible line. I personally believe that Nazarbayev behaves this way – meaning embarking on an open pursuit of his former son-in-law – only when he feels threatened, either politically or personally. So some evidence had to have reached him, as it did when he similarly acted against Aliyev in 2001, of Aliyev mounting a challenge to his person or his job. But unlike in 2001, this time Nazarbayev believed it was too much and decided to remove what he saw as a cancer (including - I believe - having forced his daughter, Dariga, to divorce Aliyev and quit politics if she wanted any political future some time down the road).

It’s not a new stage, in that it does not suggest a monumental shift in how politics are done in Kazakhstan. But neither is it business as usual because there’s no case there or in the Caspian’s other sultanate – Azerbaijan – of effective regicide.

Another dimension is whether Aliyev’s politics-in-exile, his attempts to slander Nazarbayev, will succeed. Whatever disclosures Aliyev makes, such as his accusation that Nazarbayev ordered the assassination of Altynbek Sarsenbayev, will have a skeptical audience because of his own past. Aliyev’s career in Kazakhstan I think is finished.

Is Timur Kulibayev, the second son-in-law, interested in politics? He will be interesting to watch.

Steve’s new book, "The Oil and the Glory," is available for purchase in major bookstores or through major online book sellers.