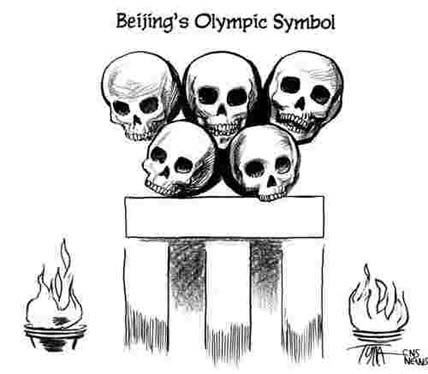

The Uyghurs and the Olympics: Will Global Focus on Beijing Bring Attention to the Plight of the Uyghurs?

The “Global War on Terror” (GWOT) has been very hard on the Uyghurs. Taking advantage of the September 11th terrorist attacks on the U.S., the Chinese government since 2001 has stepped up its repression of Uyghur dissent both inside and outside China’s borders, justifying its actions by branding Uyghur nationalists as terrorists. More importantly, however, the Chinese government has effectively gained the tacit approval of the international community for these actions by linking its repression of Uyghurs with the international efforts of GWOT. While western governments have continued to softly criticize China’s repression of Uyghurs, the August-September 2002 designation by the U.S. and U.N. of a little known Uyghur separatist group allegedly operative in Afghanistan called the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement (or ETIM) as a terrorist organization have largely rendered these criticisms impotent.

Furthermore, any western criticism of China’s treatment of Uyghurs is undermined by the fact that the U.S. is waging its war on terrorism using many of the same tactics that the Chinese government uses against Uyghurs, including rendition, torture, and detainment without due process (including several Uyghurs still in Guantanamo without charges). For the Uyghurs, this situation is made worse through the increased cooperation between the Central Asian states and China. As a result, the once-active former Soviet Uyghur communities of Central Asia have been all but silenced by the authorities in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan while these countries continue to extradite Uyghurs on their territory who are wanted by Chinese law enforcement for separatist sentiments.

Despite this grim outlook, the international Uyghur political movement has gained an important leader in recent years with the release of Rabiya Kadeer from jail and her subsequent election as the leader of both the World Uyghur Congress and the Uyghur American Association. Kadeer, who was being seriously considered for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, is a charismatic figure who, from her home near Washington, DC, appears to be succeeding in her quest to unite the disparate voices of Uyghurs worldwide. Aware of Ms. Kadeer’s potential power, the Government of China has reacted with rage at her activism, waging continual information campaigns against her in the way they have against Tibet’s Dali Lama. Going beyond smear campaigns, the authorities in China have even jailed two of Kadeer’s sons still living in Xinjiang.

With Beijing hosting the Olympics this summer, questions of human rights in China have again come to the forefront, but the question remains as to whether this will result in increased international attention on the plight of the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs, of course, must compete with the media-savvy Tibetans and the global adherents of the Falun Gong for attention this summer, but there is another, probably larger problem they face in getting recognized by the world. They are Muslims during a time when the western world suffers from a case of acute Islamophobia, and the Chinese authorities have been quick to exploit that sentiment whenever possible concerning Uyghur relations with western states.

This is precisely why I read with skepticism an article in the Washington Post this morning, which recounted Friday’s alleged foiled Uyghur terrorist attack aimed at disrupting the preparations for this summer’s Olympic Games. According to the article, the Chinese authorities claimed that they had arrested two Uyghurs who were trying to “create an air crash” on a plane traveling from Urumchi to Beijing. While, given the desperation among Uyghurs in China’s north-west province of Xinjiang, it is not out of the realm of possibility that the authorities indeed did foil a terrorist attack, one must be skeptical of this claim for several reasons. First, as Toronto’s Globe and Mail notes in its coverage of the event, “Beijing often exaggerates the terrorist threat to justify heavy-handed tactics in Xinjiang.” Secondly, it is difficult to assess the true threat of Uyghur terrorism when the Chinese government does such a good job of limiting non-Chinese scholarly and journalistic access to the Xinjiang region where most Uyghurs live. Thirdly, while the Chinese government claims to have documented numerous terrorist attacks perpetrated by Uyghurs, none of them have been on a large scale, and all of them could be just as well explained as isolated incidents of civil unrest not connected to any kind of organized militant group. The most important reason to be skeptical of this alleged foiled terrorist act, however, is that the Chinese government stands to gain significantly in reporting its existence.

Already, the regional leader of China’s Communist Party in Xinjiang, Wang Lequan, has highlighted this alleged attack’s importance in the context of the Olympics. Sunday, Wang stated forcefully that the act was undertaken "specifically to sabotage the staging of the Beijing Olympics." Furthermore, this revelation comes just as Beijing has agreed to re-open discussions with the U.S. about human rights, an issue highlighted on the Washington Post editorial page today. While the Post did not make any link between the two pieces related to the Uyghurs and the Beijing Olympics in today’s paper, the links are apparent to those who have been following the fate of the Uyghurs over the last seven years. Like the issue of Tibet, the Chinese government views Uyghur political self-determination as a question not open to discussion. Thus, if China is to begin talking with the U.S. about human rights, they would certainly prefer to have the Uyghurs off the table. A plot to blow up an airplane might help do that.

It is my sincere hope, however, that the Olympics do bring some light to the problems facing Uyghurs in China. As Uyghurs’ voices are muffled, Xinjiang is being developed at break-neck speed with a corresponding in-flux of Han Chinese migrants. The Uyghur people and culture, which share more with former Soviet Central Asians than with Han Chinese, are inconvenient obstacles to China’s mass development push westward much as the Native Americans were a century and a half ago as America expanded westward. This process in Xinjiang today is no less humane today than it was in the American west 150 years ago, and it may be even less so given the mass executions China has carried out on alleged Uyghur terrorists in the last several years. While some, especially those making millions off of China’s economic explosion, may dismiss the destruction of the Uyghurs as an unfortunate side-effect of the inevitability of progress, surely mankind has learned a thing or two in the last 150 years about giving indigenous peoples a voice in the development of their own lands. Since the Chinese do not even recognize the Uyghurs as the indigenous people of their own land, such arguments may not carry water in Beijing, but they could be highlighted in the media while the world is being stunned by Beijing’s new Olympic architecture. Perhaps NBC could take some time out between athlete profiles to interview Rabiya Kadeer while they ponder the millions they will make off of Beijing this summer. Or, maybe more simply, the Washington Post could call a Uyghur group for comment before publishing a story about alleged Uyghur terrorist acts aimed against the Olympics. Such public recognition of the Uyghurs’ plight may not open Beijing to dialogue, but it could begin the ball of global public opinion rolling about the status of the Uyghurs inside China and the real price of China’s place in the global economic machine to human rights. One does not need to look as far west as Darfur to question China’s stance on genocide in the world today; they could just as well look to China’s backyard and what is presently going on in Xinjiang.